Joanna Margaret Paul

Bio.

The work of Joanna Margaret Paul occupies a unique position in the canon of New Zealand art. The daughter of artistic and literary Hamilton publishers Janet and Blackwood Paul, her upbringing, as well as her art education under Colin McCahon, Greer Twiss and Tom Hutchins at Elam in the late 1960s, gave her a grounding in the modernist canon that was to inform her work throughout her life. Bonnard, Morandi, Matisse and de Kooning were artists whose works she found strongly influential, but her work also contains elements that, as Jill Trevelyan notes, are characteristic of a postmodern approach, such as “her unease with conventional framing devices, the centrality of language in her work, her interdisciplinary approach to artmaking and [her] commitment to feminism and environmentalism.”

Paul’s practice encompassed a range of media. She returned time and again to painting and drawing as the backbone of her creative life, but also produced notable experimental film works and wrote poetry, both of which deal with similar themes to her graphic works. Her films are particularly interesting for their insight in to her creative process. Often, Paul chose to shoot scenes that contain little or no movement—tableaux over which her camera roams in close-up, a process of directed looking that corrals and coordinates the viewer’s response to the visual scene. Paul uses the technology of the film camera not to record the movement of objects through space, but to record the movement of the eye: to make us see as she sees, and to immortalise an ephemeral act of looking.

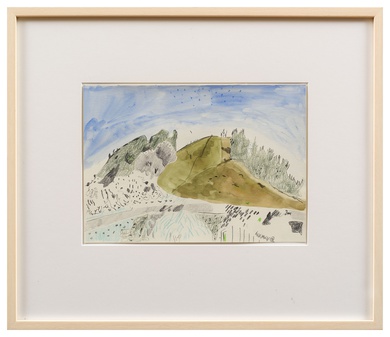

The drawings likewise unique observational acts, preserving the oblique, individual dynamics of the eye as it travels over a scene or around the contours of an object or body. Paul’s drawings and watercolours are almost startling in the “ordinary-ness” of their content. Her choice of subject matter reflects an interest in the everyday, the ephemeral and the overlooked: a view out of a moving vehicle, pieces of a child’s game, a snapshot view of suburban rooftops, and people—people in unguarded moments, at rest, thinking, captured in the private instants of stillness that punctuate the busy flow of day-to-day life.

Paul’s technique is similarly focused on mark-making that is tangential and evocative. Her pencil indicates edges, corners, interstices and boundaries, often imparting form and volume to the white space of the paper. Paul’s work is fundamentally observational; it is about the way we see, and how much of the visual field we perceive is taken up with noise, emptiness and uncertainty. As Paul’s work points out, the visual world is rarely neatly framed and compartmentalised—her “snapshot” approach to drawing and painting reflects the reality of human visual perception, and is as notable for what it leaves out as what it includes. These works encourage a type of looking that is contemplative rather than analytical, and emphasises surface, tone and atmosphere.

Paul received a Frances Hodgkins Fellowship in 1983, and the exhibition A Chronology, a survey of her work, was shown at Whanganui’s Sarjeant Gallery in 1989. Paul was also awarded the Rita Angus residency in 1993. However, despite these achievements, her work remains largely unknown to the broader public; she is very much an “artist’s artist,” known for the dedication and rigour with which she pursued her art practice. Paul’s personality was perhaps incompatible with the type of self-promotion often required in order for artists to further their careers, but the quality of her work speaks for itself.

Courtesy of the estate of Joanna Margaret Paul.